So often, after someone asks "What is groundwater?", the next immediete question is "How do I find groundwater?". Well today, we're teaching you the best way we know how to find groundwater—Electrical Resistivity Imaging. First things first, we have to remember where groundwater can be found. As you know from our Groundwater Education Series, an aquifer is a natural underground reservoir of water that can be used as a water source. There are few geological formations in the ground where aquifers can occur.

Above: Watch a quick explainer video about groundwater exploration using ERI Equipment

The areas in the ground where groundwater can occur must be porous. Sand and gravel beds are porous and can contain water. Hard rock fracture zones are porous and can also contain water. Aquifers, or layers of rock and sand that contain water, can be any size, and even a small aquifer can be valuable for a farm or small village.

In the United States, the Ogallala Aquifer is one such geologic formation. It spans below the surface of nearly the entire state of Nebraska and continues south under western Kansas, western Oklahoma, and through the panhandle of Texas, nearly to El Paso. The Ogallala Aquifer is sediment (clay, sand, and gravel) left over from the weathering of the Rocky Mountains. It’s very different—and much easier—to find water in this type of soil versus hard rock, because sedimentary (sand and gravel) aquifers are typically horizontal and therefore easier to hit with a drill than a narrow vertical or near-vertical fracture in hard rock, which has to be penetrated by the drill stem.

So, how can you identify groundwater in hard rock areas?

For people across the globe, finding water in hard rock is imperative, even if it is complex. Thankfully, resistivity imaging makes the job easier.

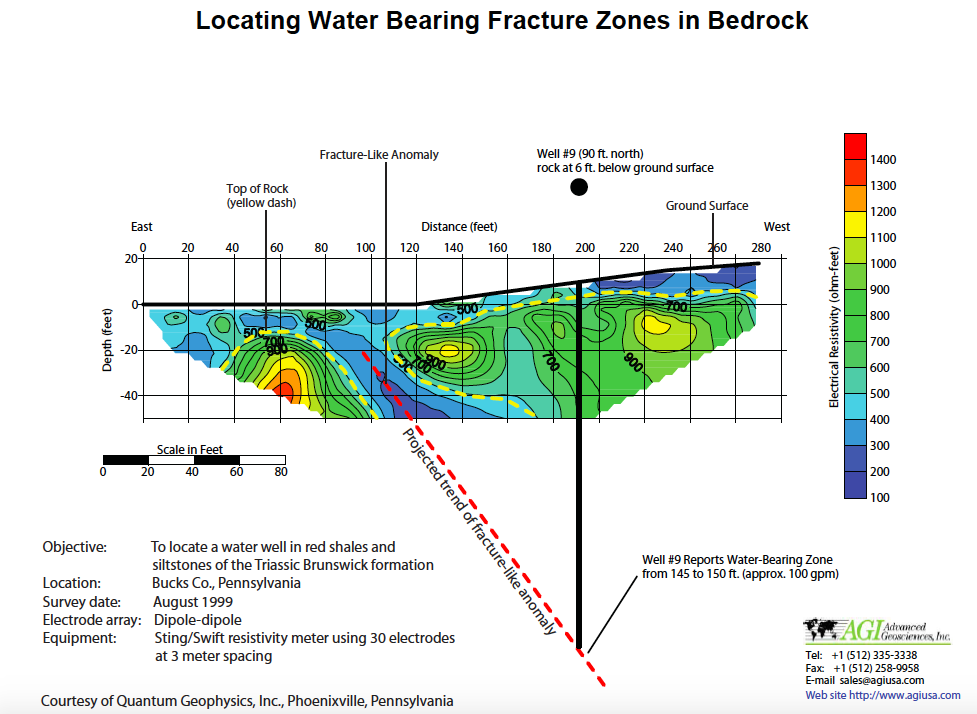

The image below is representative of the type of hard bedrock found in many places around the world, where finding water is a challenge. In such areas, water will be found in fracture zones in the bedrock. If you think of a fracture in a three dimensional way, it’s like a big sheet that cuts through the rock mass. In the example below, the dotted red line is the fracture.

The color scale shows the electrical resistivity of the ground. The resistivity of the fracture will be lower than that of hard rock, because in hard rock the moisture will collect in the fissures of the fracture zone—the blue in the fracture is lower than the green in the hard rock surrounding the fracture. So why is it lower resistivity there? Because it contains moisture, and that moisture is more conductive than hard rock.

How can you identify groundwater in sedimentary areas?

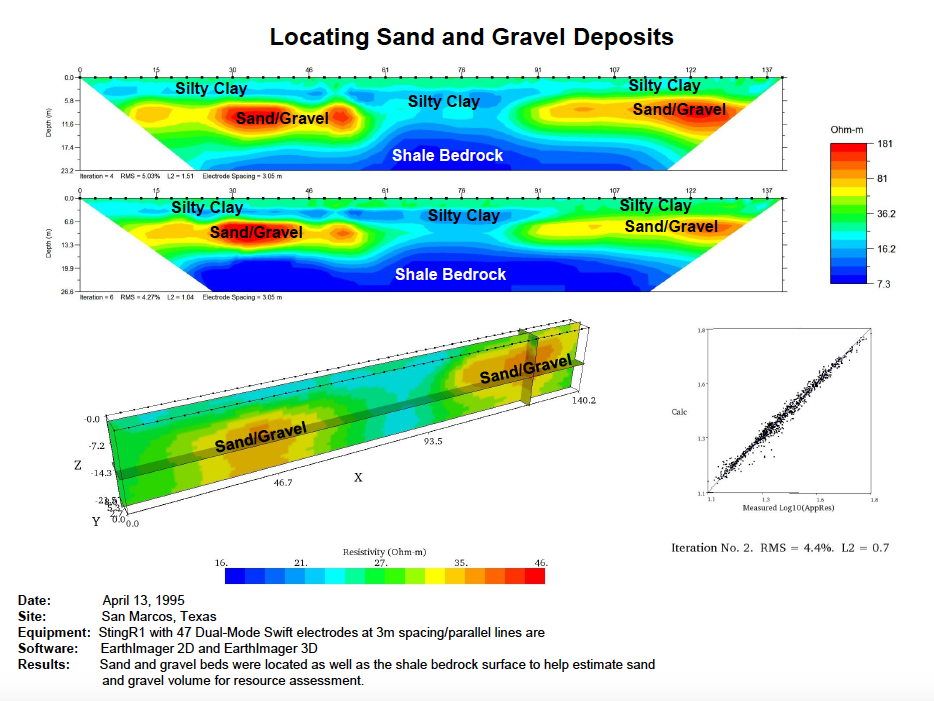

In the next example, the sand and gravel are shown in red, which means it’s somewhere between 80 and 180 ohm meters and has a higher soil resistivity value than the clay, which is in the 30s and lower.

Shale, which is a type of clay, is even lower—ranging from 7 to 16 ohm meters. Here, we’re looking for higher resistivity—the clay is more conductive (lower resistivity) than sand and gravel. This mapping shows you where you can locate the porous sand and gravel sediment beds which may hold water—these locations are where you want to drill through instead of the clay, which is very tight and does not have the permeability to let water flow.

While many of us think of clay as being wet and sticky, it isn’t permeable, which means water cannot flow through it. In fact, landfills use clay as a liner to prevent water from flowing through. For this reason, you don’t want to drill into it because there may be moisture there, but water will not flow into the well.